Just five minutes away from Debra Furr-Holden’s cluttered home office in Flint is the house she lived in as a teenager, on Pontiac Street, in a zip code that now has among the lowest life expectancies in the city: 73 years. I learned that last bit from Furr-Holden herself. She cited the figure the way you or I might describe a neighborhood by mentioning a famous building or some movie scene that was shot there. Furr-Holden is the associate dean for public health integration at Michigan State’s College of Human Medicine, and she sees the world through an epidemiologist’s eyes. Life and death are bound up in the particular conditions of place—in what Furr-Holden and her colleagues would call the social determinants of health. “Zip code,” as she put it, “is a stronger predictor of how long you can expect to live and the quality of life you can expect to live than even your genetic code.”

Furr-Holden spent a few years in Flint in the 1980s. “Things were just starting to get bad right before that,” she said. The heart had been cut out of Vehicle City. Between 1973 and 1987, Flint-based General Motors slashed 26,000 local jobs; the unemployment rate in 1988 was 19 percent. Depopulation and deindustrialization—white flight and pink slips—had reshaped what was once a booming factory town. Still, some traces of Flint’s heyday remained, Furr-Holden recalled. She got a “world-class education” in what we’d now call the stem disciplines at Northern High, part of the pipeline that conveyed new generations of engineers into the auto industry. Today, Northern’s windows are boarded up, and its grounds are full of weeds—a monument to lost opportunity.

“I watched the city come apart at the seams,” Furr-Holden said. “This was not a place that I would have ever envisioned living again, let alone raising my children.” And yet, in 2016, Furr-Holden moved back in the midst of a new calamity: the water crisis. “That catastrophic grave human injustice called me back to Flint in a way that nothing else has ever called me forward professionally,” she said, speaking in a rasp that was the result of a bad bout with strep throat in high school. “I simply couldn’t believe what was happening in Flint—the fact that nobody was really being held accountable for it. And to this day, nobody’s really been held accountable.”

Dr. Debra Furr-Holden, an epidemiologist at Michigan State, sits on the state’s task force on COVID racial disparities.

Sylvia Jarrus

Then came the coronavirus. Furr-Holden’s time in Flint, as a teen and as an adult, had been a longitudinal case study in how and why certain populations disproportionately feel the effects of civic disasters. In a way, few people in America were better prepared than she was for the arrival of a pandemic. The coronavirus presented a different kind of threat, of course. But the toll it would take, the path and shape of its destruction, would turn out to be grotesquely familiar to someone who had witnessed the uneven distributions of pain across industrial Michigan over the past half-century.

When I met Furr-Holden one May afternoon in downtown Flint, she was standing in line for crepes, wearing a KN95 mask. Over the previous year, we’d talked on and off via Zoom, where she struck a bold and imposing presence, a favorite auntie spelling out how the world works. In person, she was smaller than I’d expected. She’d traded her suit jacket and dress pants for what she called a more “bohemian” look—a tan sweater over a black shirt she’d worn the day before, and psychedelic pants. Her natural hair hid a pair of earrings made by a friend.

She watched the masked workers behind the counter as they prepared food for the predominantly white, maskless patrons inside the restaurant. Life in and around Flint had reached a new phase. People in the majority-Black city were getting their immunization shots, and mask mandates were being lifted. Concerns were festering about low vaccination rates in the conservative and predominantly white suburbs, where the virus had migrated the previous summer, like some ghoulish reenactment of the white flight of an earlier era. “I wonder how many pathogens spread with workers masked,” Furr-Holden said. This outwardly unremarkable lunchtime scene was, in Furr-Holden’s eyes, a swirling interplay of the social determinants of health—of the differing living situations of the workers and the customers, of their socioeconomic positions and their educations and their access to care, of the crushing effects of racism on some and the advantages derived from it by others.

From the start, Furr-Holden was central to Flint’s efforts to fight the coronavirus. In April 2020, the state created a task force targeting racial inequities in the pandemic, and a local group was formed soon after; Furr-Holden was a member of both. At that time, Black residents were dying of COVID-19 at a staggering rate of 90 per 100,000 people—making Black residents 73 times more likely to die than white residents from the virus. The numbers quickly improved. An analysis of county data by Harvard’s FXB Center for Health and Human Rights, conducted at Mother Jones’ request, shows that by July, Black residents were nearly twice as likely to die of COVID as white residents, a dramatic decline from the pandemic’s beginning. By October, Black residents and white residents were equally at risk of getting COVID. In November, the local ABC affiliate, WJRT, sounded a triumphal note in a headline: “Flint eliminates COVID-19 disparity among African Americans.” It was a signal achievement during a pandemic characterized by asymmetrical outcomes.

How did Flint close the gap between Black and white suffering under COVID? We may not be able to pinpoint which specific measures flattened Flint’s disparities, but there is no mystery about the strategy under which they were pursued. Furr-Holden laid it out during the first meeting of the Greater Flint Coronavirus Taskforce on Racial Inequities. The message was simple: “This is what disparities are. This is what the social determinants of health are. This is what inequity is,” she recalled telling the group. “We’re not going to program our way out of these problems. People are gonna have to look further upstream and identify what are the systems and structures that give rise to these disparities, and we’re gonna have to have a lot of our actions happen at that level.” She was proposing a different way of seeing things, life and death bound up with place. She told me, “People were like, ‘Wow, never thought of it that way.’”

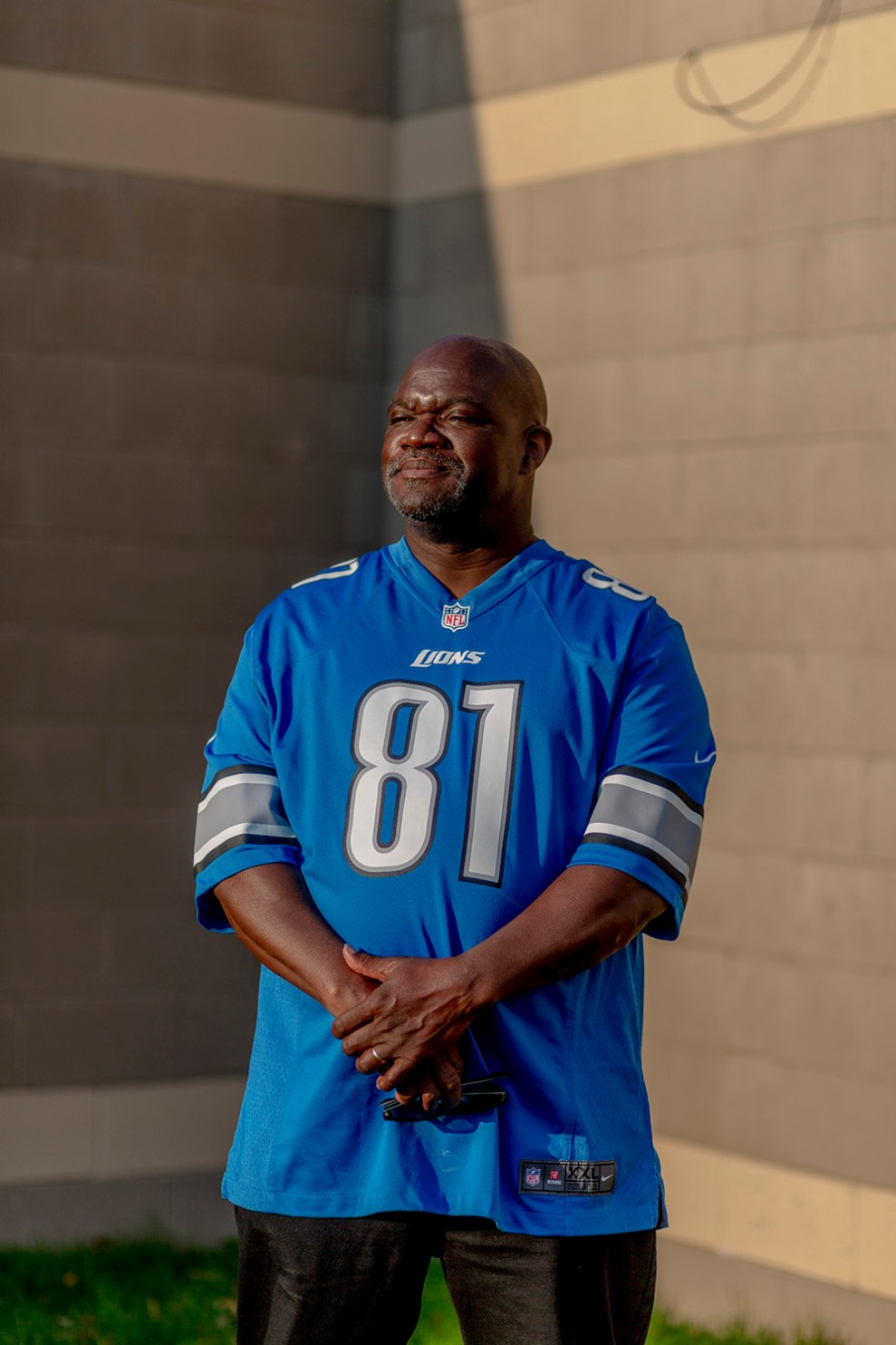

“There’s no doubt about it,” Kathy Burtley told me, her face wet with tears. “Donald Trump killed my husband.” It was May, but she was still angry about his death in April of the previous year. “I feel like I’m in the same spot,” she said. “I have those feelings just lingering.” In her house near a General Motors plant in south Flint, Kathy and her son Chris flipped through a thick binder of newspaper clippings lauding calm, charismatic Nathel, who grew up impoverished in Cairo, Illinois, and later became Flint’s first Black school superintendent.

Chris is a 30-year-old attorney who bears a striking resemblance to his father—same furrowed brow, same retreating hairline, same air of laid-back contemplation. His practice involves settling supply-chain disputes, and not long after the outbreak of COVID-19 Chris began speaking with businesses in China and Europe about how their operations were affected by the virus’s spread. On January 21, while Donald Trump downplayed the possibility of a pandemic, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention confirmed the first COVID case in the United States. “Even though we’re not doing anything in the United States, I see it moving, and I know it’s real,” said Kathy, a retired teacher. She knew she didn’t want Nathel, who was 79 and had Alzheimer’s, to wind up in the hospital.

That March, members of the Church of God in Christ, the nation’s largest Black Pentecostal congregation, convened in Detroit for the 91st Annual Ministers & Workers Conference. In Flint not long after, more than 100 people attended a musical event at Jackson Memorial Temple Church of God in Christ. Those gatherings created a “perfect storm,” says Kent Key, a health disparities researcher at Michigan State and a member of one of the COGIC churches. Over the course of a week, Flint lost four church elders: Bishop Robert Earl Smith Sr., Kevelin Jones, Philip Parish, and Freddie L. Brown Jr. “You have the shutdown,” Key said, “but then you’re finding out every day, every moment you get on Facebook, somebody just died, or someone got tested positive. And then a week later, they’re gone.” [/inline_image]

Later that month, Chris noticed his father coughing. Nathel soon felt feverish and struggled to take his medication. Chris suspected his father had come down with COVID but wasn’t sure how. Nathel hadn’t gone to either event. Testing was scarce. On March 20, Kathy called an ambulance, insisting that emts wear masks before they enter the house to take Nathel to Hurley Medical Center. Not long after, Kathy felt chills. Her head ached, and her sense of taste was gone. Nathel “was the only one who got tested in the hospital,” Chris said. “But she certainly had it.” For nearly a week, his father remained sharp. At home, Kathy watched the news from New York, where people were dying by the hundreds. She panicked, hoping that the hospital would not put Nathel in a refrigerator truck like those COVID victims she saw on TV.

“Donald Trump killed my husband”: Kathy Burtley and her son Chris still mourn the loss of Nathel Burtley, one of Flint’s first official COVID victims.

Sylvia Jarrus

The worst part for Kathy was the separation. “You cannot go in, and you cannot visit, and you cannot see, and you cannot do any of the things that you do going to a hospital,” she said. “I don’t remember all that I felt because the person I love is in the hospital, and I can’t go out there to see him. I can’t find out how he’s doing. So I’m the last thing on my mind.” When Kathy started to feel better, she would walk around the parking lot, clocking 3 miles a day. Each time she reached the hospital’s front entrance, she would recite a prayer.

Soon, Chris got the call from the hospital: Nathel’s health was rapidly declining. The family needed to see him. The roads were largely empty on the drive to Hurley as a curfew and stay-at-home orders had descended upon the city. Except for staff, the hospital’s halls were empty. “You think of being sick in hospital—I think the picture you have is being surrounded with visitors,” Chris said. “Every person in every room is there for a broken leg or are going to have a baby or have COVID. They literally are just there by themselves.”

In a surreal reunion, the Burtleys met in the hospital parking lot, masks on. Chris’ brother had flown from Colorado. His sister had driven up from Detroit. They went to their father’s room, where he lay alone, unconscious, attached to a ventilator. Chris and Kathy marveled at how good Nathel looked. Chris’ sister sang the hymns Nathel loved. “It was nice to see everyone,” Chris said. “But in the back of your mind, you’re going to see a person you’re probably not going to see again.”

On April 6, a week before his 80th birthday, Nathel Burtley died. Around that time, Ruben Burks, a longtime labor activist who served as the first Black secretary-treasurer for the United Automobile Workers, also died of COVID. They were among the first official pandemic deaths in Flint. “It gave a lot of people in our community a very real sense that this thing is here,” Chris said of his father’s death, “and it’s going to impact us.”

Nursing student Katie Wrenn talks with Donald Boyce, 60, before his vaccination in April.

Sylvia Jarrus

Isaiah Oliver was attending an executive coaching session in Aspen, Colorado, when he heard that “all hell broke loose” back home in Flint. The 40-year-old president of the Community Foundation of Greater Flint, a nonprofit charity that gives grants to local organizations, had always felt connected to the city’s struggles. He saw them all—the white flight, the years of economic disinvestment, the water crisis—as part of the same continuum, dependent clauses in the long-running story of racism in Flint.

This, too, was a different way of seeing things. The widely embraced narrative of the city is that it enjoyed a golden era in the first half of the 20th century, powered by the growth of General Motors, then was brought low in the second half by—take your pick—racist reaction, bad municipal governance, political demobilization, and, of course, deindustrialization.

For some Black folks, the Flint narrative looks a little different. The color line runs through the center of the city’s history, in boom times and bust. The vibrancy of Flint’s public life—its “community education” system, for instance, which turned schools into neighborhood civic centers—grew out of the solidarities created by segregation, as historian Andrew R. Highsmith has pointed out. The city’s collapse came with the dispersal of those solidarities to the suburbs, beginning in the 1940s with GM’s decision to build new plants there and not in Flint proper. In the 1960s, picketers had a slogan that evoked the company’s racist history, from its central role in building segregated housing around the city to its discriminatory employment practices: “Jim Crow Must Go, GM Crow Must Go.”

The coronavirus, as Oliver saw it, was part of that same legacy. On his flight home, he drafted two proposals for his foundation: a plan for an urgent COVID relief fund to support residents’ needs and a design for what would eventually become the Greater Flint Coronavirus Taskforce on Racial Inequities. Upon returning to Flint, he started making calls to people in his network—from health care operators and community organizers to local activists and faith leaders. As the task force took shape, he said, “we quickly realized through conversation it wasn’t just about differences in the numbers” for the coronavirus. It was about the underlying causes of those disparities “in the numbers for Black and brown folks, no matter what it is, whether it’s the water crisis or public health pandemic or political polarization or any other thing that plagued our community.”

What Flint needed was some social medicine. Oliver and his team were drawing on an old model of public health, one that for a time had fallen out of the American mainstream. The spirit of the approach was captured by Rudolf Virchow, a 19th-century German physician and a forebear of modern pathology. “Medicine is a social science,” he said, “and politics is nothing else but medicine on a large scale.”

Virchow’s aphorism had grown out of an investigation he conducted on behalf of the Prussian government into a typhus epidemic in the late 1840s. He had concluded that the terrible effects of the outbreak were rooted in material and cultural conditions. “Medicine has imperceptibly led us into the social field and placed us in a position of confronting directly the great problems of our time,” he wrote in his report. A “free, educated, and well-to-do” populace would not have been as vulnerable to the ravages of disease as were, alas, the millions “of our fellow citizens who are at the lowest level of moral and physical degradation.” He proposed a “radical” intervention along several dimensions at once: democratizing the economy, decoupling the church from the schools, reforming agricultural techniques, inculcating “freedom to the greatest extent, especially complete liberty of communal life.” Virchow’s recommendations were rejected, and he fell out of favor with the Prussian authorities.

But the larger cause of social medicine was being taken up by crusaders of all stripes, reactionary and reformer and revolutionary alike. Diseases in those days were believed to originate in miasmas—noxious air emanating from rotting animal carcasses and other kinds of filth. To prevent epidemics in crowded, rapidly industrializing cities, it was imperative to address the squalid conditions in which poor people lived. Public health interventions were viewed as inextricable from social and political interventions. Tuberculosis was an issue of housing density as surely as it was an issue of the lungs. The disease theory underlying the new consensus might seem laughably misguided today, but it enabled a holistic and interdisciplinary approach to attacking contagion, with civil engineers and chemists teaming up with physicians and social reformers to do, as Virchow had put it, “medicine on a large scale.”

Soon enough, however, public health left the streets and sequestered itself in the laboratory, turning away from structural approaches and their emphasis on social determinants. “The old public health was concerned with the environment; the new is concerned with the individual,” public health official Hibbert Hill said in 1913. At the time Hill’s statement was less descriptive than it was tendentious. But the germ theory of disease and the rise of bacteriology, along with the collapse of progressivism, had created the conditions for a new model of public health to take hold, one steeped in the high science of the laboratory, as public health historians James Colgrove, Amy Fairchild, and David Rosner have argued. Under the new paradigm, public health focused less on unhealthy social conditions than on unhealthy personal behaviors. Social reform could be cordoned off from public health now that highly efficient apolitical interventions such as vaccines and antibiotics were available.

By the time Furr-Holden entered the PhD program at Johns Hopkins in the 1990s, public health was hotly contested ground. Even among people who accepted the idea of social determinants, there were divisions. Dr. Camara Jones, who joined the CDC in 1994, recalled that there were people “getting funded to have meetings about social determinants of health [who] would never talk about racism at all.” Internal working groups on social determinants and racism were separate, said Jones, an epidemiologist and now a visiting presidential fellow at Yale’s School of Medicine.

Public health’s transition from the social to the personal reflected similar movements in the political culture. Likewise, the resistance to the individualistic turn tracked with other forms of political dissent and collective action. Prominent public health officials worked with civil rights groups, established health centers for poor Black Mississippians, and fought alongside the United Mine Workers to combat black lung disease. By the 1970s, researchers were criticizing the narrow focus on individual risk of disease, and physician John McKinlay was making the “case for refocusing upstream” on the political and economic causes of illness.

True public health initiatives just couldn’t be run out of a lab. “A new cancer medication, they’re going to be developing it in a petri dish, and they’re going to be testing it out in the laboratory with some other type of creature that’s nonhuman—primates or mice or something like that,” Furr-Holden said. “Those primates and those mice are not living under the same kind of conditions that human beings are living under. They’re living in ideal laboratory conditions. I’m like, why don’t you put that mouse in a stressed environment, feed it a high-fat, high-sugar diet? Why don’t you disrupt his cancer treatment the way women’s cancer treatment gets disrupted, because they can’t afford the copay? You’re testing things in ways that don’t mirror, in any way, shape, or form, the real world.”

Furr-Holden considered becoming a medical doctor but found herself drawn to the social circumstances underlying the suffering of people she encountered. She thought about her own family and their history of addiction, like her uncle Raymond in Washington, DC, a heroin user and alcoholic who had both of his legs amputated and whose struggle to overcome addiction was tied up in his lack of stable housing and health insurance. “It’s less for me about what happened in your childhood that makes you use drugs now,” Furr-Holden said. “It’s more like, how do we create environments for people when they’ve had problems with drugs?” That sort of questioning would underpin all her work in public health, but at the time, she recalled, it ran crosswise to the field’s consensus. “I wasn’t learning about rural health disparities. Back then, you know, we weren’t talking about the intersection of race and class. We used to treat race and class like nuisance variables, like noise,” she said. “‘We will control for them. We will control them away and say, well, A is related to B after controlling for race and class.’ We treated it like it was no big deal. Now we know we need to understand how these things work so differently for people based on race or based on class. That’s a very different way of trying to solve problems.”

Furr-Holden talks about “algorithms” of access: who gets screened, who gets mobile testing, who gets admitted to hospitals, and who gets “do not resuscitate” orders. After the outbreak of the coronavirus, she said, the algorithms “were literally killing people—killing our people.” The pandemic called for a return to social medicine, for action targeting not just the disease itself but the root causes of its disparate effects. But that approach works against the grain of the individualistic model, which, for all the challenges to it, has endured into the 21st century. Recently, Rochelle Walensky, director of the CDC, tweeted that “your health is in your hands.”

Early on in the pandemic, Michigan had the fourth-highest COVID mortality rate for Black residents, at 328 deaths per 100,000 people. But in Genesee County, where Flint is located, maps depicting the hotspots showed that deaths were especially pronounced in the city’s north and west sides and two neighboring townships. Rick Sadler, an assistant professor of public health at Michigan State’s College of Human Medicine, saw the early patterns as a “social network phenomenon” in Flint’s northwest, a landscape of single-family bungalows and vacant properties that’s home to the city’s most densely populated Black community and some of its poorest neighborhoods. Churches, Sadler told me, were northwest Flint’s “biggest anchor.” Sadler grew up in Flint. He thought about the church he attended in Flint’s south end, how it drew people from within the neighborhood. But as neighborhoods changed over time—freeway development and “renewal” projects in the 1960s, for instance, displaced thousands of Black families—the people who attended such anchor churches would spread throughout the city and county. “So if we had all gone to church and infected each other, we would have then spread it to seven different towns and townships and cities,” Sadler said.

The task force advocated placing testing sites closer to where community members were most affected. Local health providers also offered mobile testing units in neighborhoods hit hard by the water crisis. Four prominent churches were turned into testing sites.

Among them was Shiloh Missionary Baptist Church, a sprawling single-story building in north Flint. Back in September 2015, in the throes of the water crisis, the Rev. Dr. Daniel Moore and his congregation handled truckloads of bottled water for community members for six hours each day. That moment of collective action, as community groups looked to one another for aid, laid the foundation for similar collaboration when COVID struck. “I tell people that the Flint lead crisis was a dress rehearsal for what we’re going on now,” Dr. Lawrence Reynolds, the city’s health adviser, said.

It would’ve been unthinkable at the time to suggest that the water crisis could have somehow helped Flint residents in the next public health catastrophe. After the Great Recession, Michigan officials diverted tax revenue away from ailing cities to fill the state’s own budget holes. In April 2014, despite pleas from local and state officials, state-appointed emergency manager Darnell Earley switched water sources from the Detroit River to the Flint River to save money, leaving residents with lead-contaminated water. As Anna Clark, author of The Poisoned City: Flint’s Water and the American Urban Tragedy, wrote: “Among the many ravages attributed to the water crisis—the rashes, the hair loss, the ruined plumbing, the devalued homes, the diminished businesses, the home owners who left the city once and for all, the children poisoned by lead, the people made ill or killed by Legionnaires’ disease—perhaps the most devastating was that people lost faith in those who were supposed to be working for the common good.”

Terraca Rogers remembers what that was like. When the water crisis hit, Rogers recalled, she and her children were living on Flint’s south end, in what’s sometimes known as Little Beirut. They broke out in rashes from the contaminated water. Lacking a car, they had bottled water delivered to them to use for cooking, cleaning, and washing. Rogers still uses bottled water to this day. “You believe in something, and then all of a sudden something happens, and now you’ve just lost trust and faith,” she told me while waiting in line with her children at Shiloh for their first vaccinations. “You don’t want to go back to it.”

Churches like Salem Lutheran Church were vital pieces of public health infrastructure during the pandemic.

Sylvia Jarrus

Pastor Daniel Moore of Shiloh Missionary Baptist Church says the water crisis and the pandemic have a lot in common. “The distrust and frustration,” he said, “are similar.”

Sylvia Jarrus

The Flint community mobilized to fill the void. “When the water crisis happened, grassroots organizations and neighborhood associations began to work together in capacities that they had never worked together before,” MSU’s Kent Key said. Church leaders became “first responders” for the water crisis and distributed food and bottled water. Residents protested at meetings and worked with outside experts to collect and test water samples. That work taught residents to listen to trusted community messengers in lieu of a government that had effectively failed them. “This network,” said Reynolds, referring to the Flint community’s COVID response, “was built based on how we had to respond to the Flint water crisis when we were completely on our own.”

When the pandemic arrived years later, the community’s informal infrastructure was ready once again to do the work state and local government couldn’t—or wouldn’t—do. To contend with shortages in personal protective equipment, community organizations stepped up to provide masks of their own. Trusted community members worked with the county health department as “health navigators” and went to specific neighborhoods to distribute masks, hand sanitizer, and information about testing. Flint’s foundations and its chamber of commerce funded targeted grant programs to keep Black- and Latino-owned businesses afloat when they couldn’t secure PPP loans. The money gave businesses the ability not only to purchase protective equipment for workers but also to protect their payrolls, allowing workers to keep their jobs. They even funded cash-assistance programs to help pay for people’s rent and utilities. “What’s predictable for us is the state and our philanthropic community will backfill a lot of these financial gaps that have been left by COVID,” Furr-Holden says.

Flint Mayor Sheldon Neeley, who grew up in north Flint, listened to his health adviser and suspended water shutoffs to residents who couldn’t pay their bills. Gov. Gretchen Whitmer extended a stay on evictions and created a diversion program that allowed landlords to collect up to $3,500 in unpaid rent so long as they didn’t evict their tenant.

In November, an outside case study by the National Governors Association Center for Best Practices and the Duke-Margolis Center for Health Policy praised Michigan’s efforts to reduce racial disparities. The average COVID cases among Black residents fell from 176 per million people per day in March 2020 to 59 per million people per day in October 2020. The gap for Latino residents had narrowed as well. “Strong leadership, sustainable infrastructure, accurate data and targeted strategies are key to addressing racial disparities and inequities during COVID-19 and beyond,” the report concluded. (Jon Zelner, an epidemiology professor at the University of Michigan, also points to rising case and death rates among white residents after state lockdown restrictions were lifted at the end of June 2020.)

But Furr-Holden was worried. During the holidays, just like the rest of the country, Genesee County saw an uptick in COVID cases and deaths. Furr-Holden warned me that all the work to close disparities was at risk of coming undone. She showed me a before-and-after map of Genesee County. October, the before image, looked like a Rorschach test, with Flint at the center coated in light blue except for a darkened west-side neighborhood and blotches of dark blue in nearby suburbs. By November, it was as if blue paint had spilled everywhere as the virus spread. Local and state interventions could do only so much absent large-scale federal measures such as juiced unemployment benefits.

“We’re trending in the wrong direction,” Furr-Holden said. “The big why is because people aren’t able to effectively shelter in place because they have to work because we lost enhanced unemployment.” For months, lawmakers in Washington jockeyed over another stimulus bill, causing a void in economic support for Americans. “We need another stimulus package,” she said.

A National Guard specialist takes the temperature of two Flint residents before they enter Shiloh Missionary Baptist Church’s vaccine clinic.

Sylvia Jarrus

By the spring of 2021, a new variant was driving another surge in Michigan. The task force faced a new problem: What happens when people in the surrounding whiter, more conservative suburbs refuse to get vaccinated? It was a question that Isaiah Oliver heard from community members during a video conference call one May morning. Oliver settled into his office chair beside photos of his kids, his wife, and Malcolm X. From his office you could make out the iconic red brick of Saginaw Street, which cuts through downtown Flint. Images of Mayor Neeley and his wife, state Rep. Cynthia Neeley, flashed on a billboard with messages urging residents to stay safe and wear masks. They hovered over gray statues of the founding fathers of Flint’s auto industry.

The task force had allowed me to join its typically private meeting from Oliver’s office, provided I not quote people directly without their permission. On this day, the conversation centered on how to get more people vaccinated. County health officer Pamela Hackert shared information on how rates broke down across the county. Inside Flint, rates were still low but steadily improving. But in the suburbs, vaccine acceptance remained low. From his father’s office, Chris Burtley, who chaired the group’s philanthropy subcommittee, worried that unvaccinated people flowing through the city would mean Black and Latino residents would disproportionately suffer.

Their solution? Apply what worked in Flint to the suburbs and tailor it. Get health navigators to reach out directly. Put vaccine clinics in specific areas. Build connections with suburban faith communities and have them act as messengers. The way they discussed it, Flint served as a model for the county.

Little had been decided in that meeting, but Furr-Holden later told me she questioned whether the model could succeed without the right people to work across racial lines. “We have the model. What we don’t have are the messengers,” she said. “It’s just so telling, because a lot of white folks who do the work alongside some of the Black folks in Flint are seen as ‘not like us’ to their white counterparts in other municipalities in the county. They’re like, ‘You’re on their side.’ This is not just about race. This has come down to race, it’s come down to values, and it’s come down to political party and political affiliation, and if you don’t fall on the right side on all of those things, you’re othered. It’s going to be our problem. We’ll have to figure it out.”

Getting “upstream” of the disease itself, to the political-economic factors that enable its spread and amplify its effects, was hard work. Furr-Holden was under no illusions about why. “We’ve never been honest as a nation about how truly inequitable our society is—how the systems and structures are set up by their very design for some people to prosper and have better access and more opportunity than others. And there’s a cost to it,” Furr-Holden told me. “So many Black and brown people, so many rural communities, getting hit so hard by this pandemic has cost our nation millions if not billions of dollars. Inequity has cost us tremendously. All those Black and brown people that then were fighting for beds and ventilators and hospitals were the reason some of these nice middle-class and wealthy white folks weren’t able to get on those ventilators. Literally, inequity costs us all.”

Janice Rorie, 55, gets her second shot. Rorie knew several people, including her nephew, who died of COVID.

Sylvia Jarrus

One Sunday in May, I stopped by Shiloh Missionary Baptist Church for the first in-person worship service since the beginning of the pandemic. An elderly woman was greeting patrons and asking them to fill out a health screening form, the sound of guitars and drums echoing around the sanctuary. She took their temperatures before ushers led them into the sanctuary, where 70 or so people were singing and moving to the words of the Lord.

Each pew was cordoned off to ensure family units sat 6 feet apart from each other. In one, I noticed Mayor Neeley scrolling on his phone, sitting with his mother. I grew up Catholic, so I was unaccustomed to the less-structured service—the hallelujahs and amens, the older Black women in flowy dresses swaying and waving their hands to the music coming from a maskless and socially distanced choir.

That’s when the unexpected happened. I saw tears falling down one woman’s face. She couldn’t muster the words even as the rest of the small choir continued on. Rev. Dr. Daniel Moore dabbed a handkerchief to his eyes, and then approached the podium and joined the choir, his bold, deep baritone suffusing the room.

Soon Moore would launch into a sermon that was as much a public health address as it was a religious oration, thanking God for giving epidemiologists an understanding of the virus’s true nature, but none of it could compare with the gravity of this moment. After 14 months and 867 deaths in Genesee County alone, dozens of people had gathered for the first time in their place of worship, with joy in their voices. During the crisis, by necessity, Shiloh had offered an all-too-literal sort of salvation; it was a place for people to get tested and immunized. Today, the church could address itself once more to the social medicine of the soul.

Nathel Burtley, Flint’s first Black school superintendent, died of COVID in April 2020. He was 79.

Sylvia Jarrus

"between" - Google News

July 27, 2021 at 05:03PM

https://ift.tt/3f1hidD

How Flint Closed the Gap Between Black and White Suffering Under COVID – Mother Jones - Mother Jones

"between" - Google News

https://ift.tt/2WkNqP8

https://ift.tt/2WkjZfX

Bagikan Berita Ini

0 Response to "How Flint Closed the Gap Between Black and White Suffering Under COVID – Mother Jones - Mother Jones"

Post a Comment